After Iceland, there was La Palma. It could have been the Azores, of course. There are more than just two volcanic archipelagos and islands in our youngest ocean, the Atlantic Ocean. But it was La Palma. Could we have seen it coming? Eruptions at La Palma are about ten times less frequent than at Iceland, perhaps two or three times per century. Still, it would happen eventually. And to put it into perspective, the chances of an eruption in La Palma were much higher than one in Reykjanes.

The eruption began on Sunday 19 Sept, at 3:12pm, with a small bang. As is common in La Palma eruptions, the dike which had reached close to the surface was contained by the older lava flows above. Eventually the pressure reached breaking point, an explosion occurred which blew out the old lava (the brown clouds), and an opening was made for the new lava to come out. It happened on the west facing slope of the Cumbre Vieja volcano where two fissures formed, each about 200 meters long. At peak there were 11 vents in action but one vent became dominant. (Steam is apparently still rising from other vents though.) A common aspect of La Palma eruptions is that the vents form near the cones of previous eruptions, possibly because the ground there is easier to break through. This eruption too came from an area riddled with previous eruption cones, and the current vent is next to an old cone (now presumably buried). Disastrously, the erupting vent was on a slope above and close to a populated area. The lava is relatively cool and slow flowing, but as of this morning, 390 homes have been lost. A thousand people may now be homeless. A few houses may have been second homes (still a terrible loss – in spite of some comments made, most owners of holiday homes are not rich) but for the large majority the house will be everything those people possessed. We live at the mercy of the earth.

The ESA emergency satellite mapping service sprang into action. Images of the flows show the location and expansion better than the ground based press ever could. This is not a tourist eruption and we do not have the wealth of images and videos that Iceland has produced. Those are for ‘nice’ volcanoes, not for human disasters.

Eruptions here are not highly explosive. Still, it seems to be evolving towards a bigger bangs. The eruption rate is not too high (perhaps 50 m3/s) and that also is helpful.

How will it continue? Previous eruptions have jumped between different vents at different times and that could happen this time as well. And previous eruptions have lasted between 24 and 84 days – we still have a way to go.

La Palma

The Canary Islands are a group of larger and smaller islands, are volcanic, and are located off the coast of southern Morocco. We know one of them very well from previous activity: the submarine eruption of El Hierro, south of La Palma. Tenerife has the largest volcano and Lanzarote had the longest lasting historical eruption. The entire region remains active. This differs from a conventional hot spot where one may see extinct volcanoes further from the current location of the spot. Here the heat is distributed over a larger area. There is however a bit of a gradient, in that La Palma is still in the shield building phase while islands to the east did that a long time ago. The heat may be slowly migrating west.

The fifth largest of the Canary Islands, La Palma is mountainous. The roads make for interesting driving as they wind up the sides of the mountains. Seeing upside down cars is not uncommon (on one drive I saw two). One main road goes underneath an active volcano by means of a tunnel: this may be a unicum, but do drive carefully especially when exiting the volcano (where I saw one of those two overturned cars).

From the Digital Terrain Model of the National Geographical Institute of Spain (reduced resolution). Sourced from https://www.turbosquid.com/3d-models/island

The mountains form an impressive volcano. The peak is 2430 meters above the sea level but this underestimates the true size of the beast. The base of the volcano is 4 kilometers below sea, making it over 6 kilometers tall. Submarine volcanoes have an advantage as they can grow much steeper and the water helps carry the weight. They grow faster and taller than their aerially exposed counterparts. Still, this is a large one.

La Palma is a complex island with multiple volcanic features. It has history. A history of five volcanoes, in fact, all of which can still be seen on La Palma.

The map above shows that there are two obvious volcanoes. The northern, large one with a hole in its side is called Taburiente, and it is extinct enough that an astronomical observatory has been build on its peak. (Mind you, another one is build on Mauna Loa.) The big hole is called the Caldera de Taburiente. Standing on the top, the Caldera is very steep (I know from experience). The smaller ridge volcano to the south is Cumbre Vieja, and it is clearly not extinct as it is currently erupting. There is a saddle between the two volcanoes called Cumbre Nueva. Cumbre Vieja, in spite of its name, is the younger of the two: the names ‘Vieja’ and ‘Nueva’ refer not to the ages of these ridges but to the forests on them.

La Palma is quite a rainy island (tourists beware: the beauty of the greenery gives a hint), and erosion has carved deep valleys in the sides of the volcanoes. These are locally known as ‘barrancos’. The barrancos on Taburiente are deep and steep (causing difficult and bendy driving here), whilst they are much less prominent on Cumbre Vieja. Cumbra Vieja is young whilst Taburiente is old and weathered, as lined as the faces of the people I once saw going to work in the cold of Novosibirsk.

But there have been volcanoes here before. The steep sides of the Caldera de Taburiente have cut through the layers that make up the volcano. Not all those layers are from Taburiente: some are much older than the current volcano. Even the old can be young, when seen in comparison to those who came before. We so easily forget that no one feels as old as others think they are: we perceive our own age from our memories. But we all are old at heart: our memories give life to people who may have long since passed away. They haven’t really passed on, until all living memory of them has ended. La Palma has kept those memories of the departed, and has brought them to the open. Let’s dive in.

Submarine volcano (unnamed)

The oldest lavas that are exposed in the Caldera formed under water: pillow lavas are seen, interspersed with tuff and sediment. There are also intrusive rocks that formed from magma injection underground, with many dikes running through them. Although all this formed under water, nowadays they are on dry land: the layers were uplifted later to above sea level. In the Caldera they are seen as high as 400 meters above sea level. Some of the lava flows formed in deep water, other in shallow water: the uplift continued while the subsea volcano was active. We normally think of uplift (also called inflation) as coming from growing magma chambers in the crust. That is part of it, but uplift on this scale has a deeper origin. The mantle and lithosphere below are heating up as a hot spot moves underneath. Hotter rock has a lower density and therefore floats higher, like a cork in the bath. Everything above rises too as the heat increases. This is the main process that causes large scale uplift in volcanic regions, and it is also the reason that when the hot spot moves on, the island it created begins to sink. If you live on a volcanic island, a volcano that stops erupting can be as dangerous to your future as one that is actively burying your land.

Exactly when the submarine volcano first began to grow is not well known. The oldest accurately dated lava (using radio isotope dating) formed 1.7 million years ago. But micro fossils embedded in the sediments are older: 3 to 4 million years. This sounds old for a volcano that hasn’t moved much, but it is young for the Canary Islands. Tenerife is at least 7 million years old, and Gran Canarias may be twice that. Unlike Hawai’i, the volcanic activity here does not migrate, but there has been a slow shift in peak activity from east to west. Interestingly, this westward shift (2-3 cm/yr) is similar to the spreading rate of the Atlantic ocean at this location. The area has kept its distance to the mid-ocean rift and perhaps that is where it gets its heat from. The alternative model of a mantle plume has also not been ruled out though.

The submarine volcano began to grow 4 million years and by 1.7 million years ago may have become an island. The orientation of the dikes changed over this time. Originally they ran southwest to northeast, but as the volcano developed a feeder conduit the dikes rotated to a north-northwest to south-southeast orientation, similar to the north-south elongation that we still see in La Palma.

Garafia volcano

The island volcano that now formed is known as the Garafia volcano, and it is considered the second volcano of La Palma. It is named after a village on the north coast of the island. This volcano grew over a period of half a million years, between 1.8 and 1.2million years ago. It reached an impressive size: Garafia reached 23 kilometers across and was at least 2.5 kilometers tall: this was the first shield volcano. It’s lava flows are exposed not only in the Caldera, but also at the bottom of the deepest barrancos all around the current volcano. They are thin pahoehoe flows, with some explosive layers (lapilli). It was a basaltic volcano, typical for a volcanic island.

Around 1.2 million years Garafia came to an end when a large collapse occurred. In a way this was a typical event. Slope failures are common on the western Canary Islands. The most recent one was on El Hierro, 15,000 years ago: it left a scarp 1 kilometer tall. Garafia produced several such land slides which are seen on the ocean floor. It is not clear whether they are all part of the same event or (perhaps more likely) the collapse happened in several different events. One debris flow lies off the east coast and came from somewhere above Santa Cruz. Three debris flows are seen to the southwest. The four events happened between 0.8 an 1.2 million years ago, and together deposited some 650 km3 of debris on the ocean floor.

Taburiente

On the remnant of Garafia a new volcano now began to grow. It was in pretty much the same location but extended a bit further south where the land slides had removed half of the old volcano. Eventually it fully covered both the remnants of Garafia and the older submarine (uplifted) volcano.

The walls of the Caldera the Taburiente showing the older layers. Source: The Geology of La Palma

Taburiente grew for over half a million years, between 1 million and 500,000 years ago. It reached a height of 3 km, and was 25 km in diameter. Like Garafia, it was basaltic in nature. however, during its later years the eruptions became more explosive (never devastating) and the magma became more evolved. At the same time, the eruptions began to move to the south, away from the ancient location. This formed the Cumbre Nueva ridge. By 400,000 years ago the peak was extinct but this ridge continued to be active.

History now repeated itself, as it always does. The peak of Taburiente and the side of the Cumbre Nueva collapsed into the ocean around 500,000 years ago. Compared to Garafia, this was a smaller event. The debris on the ocean floor has a volume of around 100 km3. And whereas Garafia collapsed in what may have been 3 or 4 separate events, a long time apart, Taburiente only had one. The gap it created was not yet the current Caldera de Taburiente. Erosion has deepened and widened the hole since, and also formed an erosion channel at the bottom: the Barrancos de Las Angustias. And there was new growth on the far side.

Bejenado volcano.

The collapse removed a lot of weight from the southwestern part of the edifice. This allowed new volcanic activity, from decompression and from easy access to the surface. A new volcano began to grow. This one is called Bejenado, and it forms the southern wall of the Caldera. (It is interesting and perhaps confusing that the two sides of the Caldera are from different volcanoes and have different ages.) The current Caldera looks nothing like it did after the collapse: it became enclosed only because of this new growth.

Cumbre Vieja

The new volcano filled in part of the newly formed basin. The activity did not last too long. By 150,000 years ago, all eruptions were from a new volcano, Cumbre Vieja. Unlike the previous volcanoes it formed a curved ridge. It may have formed along a radial rift zone of Taburiente, activated by the southward migration of the heat. The ridge continues into the sea, with a range of sea mounts which are equally active as the part on-land. Although Cumbre Vieja is no longer young (it has reached a height of almost 2 km), it never developed an eruptive centre. The eruptions are along the entire ridge, and are monogenetic which each one forming its own rift (normally on the flanks, at a slight angle to the ridge) and cones. Eruptions are strombolian. The lava is basaltic but more evolved lavas (phonolitic, which contain a much higher fraction of silicate) are common. (The current eruption was reported to produce tephrite, a slightly evolved version of basalt.) This volcano is very different from any of the previous four. Why that is is not clear.

On the west side the ridge has a steep edge, with a coastal platform where much of the banana plantations are. The cliff is caused by sea erosion; the platform has build up from later eruptions.

Historical eruptions occurred in 1585 (84 days), 1646 (80 days), 1677 (66 days), 1712 (56 days), 1949 (38 days) and 1971 (25 days). There is no pattern to the either the frequency or location: this volcano is all over the place. There is however a pattern of decreasing length, as if it lived of a previously formed magma reservoir – we will see whether this hold his time (in which case the eruption will be over by mid October) or not (in which case it could last until December)! There was also an eruption in the late 1400’s, around or just before the time of the Spanish settlement in 1493, but we have no historical record of this.

Events high up tend to be explosive and vents lower on the flanks tend to be effusive – this seems to hold for the current eruption as well. Eruptions often occur near older phonolitic cones. For instance, the 1677 eruption was in San Antonio volcano (a tall cone) but this cone already existed before that time.

La Palma is a fascinating place. It showcases its history well. But it is not a ‘nice’ volcano. Eruptions occur over a long area, and any one location sees lava only rarely. This encourages settlement of regions that are never safe. La Palma’s eruptions are slow and they give people time to leave. This is no Taal. But they are also destructive, as we see now. In a few months time the eruption will be over and the volcano will go to sleep for decades or centuries. But it will take people affected by the eruption a long time to recover. Those memories will not go away

Albert, September 2021

This post is almost entirely based on ‘The Geology of La Palma’ by Valentin Troll and Juan Carlos Carracedo, published as a chapter in the book The Geology of the Canary Islands’ (2001).

To end this post, I am reproducing a very useful overview made on Dec 21 by VC commenter Oliver:

To keep the overview, here is a summary of the previous events and facts of the eruption on La Palma:

– The eruption began on 09/19/2021 at 3:12 pm (local time) on the lower western flank of the “Cumbre Vieja” in the area of the “Cabeza de Vaca” and just above the first houses of the village “El Paraiso”.

– Two eruptive fissures developed, each approx. 200 m long and running in a north-north/westerly direction. On the evening of September 19th, up to 11 vents were active at the same time. This released lava fountains that were several hundred meters high. The VAAC detected volcanic ash at an altitude of 3000 m. There were also some lightning.

– The released lava was relatively viscous and cold (approx. 1075 ° C) and steep cinder cones quickly developed around the active chimneys. An Aa lava flow was formed, the front of which was initially up to 15 m high, but later mostly reached a thickness of up to 6 m.

– The lava flow crossed the LP-212 road, moved at about 700 m per hour in a westerly direction into the area just north of “Monte Rajada” and grazed the center of the village of “El Paraiso”, but already destroyed numerous houses.

– On September 20, the lava flow moved further west along the “Camino el Pastelero” street and destroyed other buildings in the process. However, the flow was getting slower and slower. Since there are numerous cisterns and small canals in the area (for the the banana plantations on the coast), there were also some phreatic explosions and the generation of steam fountains, which also led to false reports about the opening of new vents in this area.

– The seismic activity decreased significantly after the eruption started.

– On 09/20/20201, eruptive activity was concentrated in a vent that had developed at the northern end of the eruptive fissure. The largest cinder cone had developed there as a result of ongoing Strombolian activity.

– On the evening of September 20, new vents opened about 900 m below (northwest) of the main cone (below the LP-212 road) at around 9:30 p.m. At the same time there was an earthquake with a magnitude of 3.8. At least three effusive vents were active. They showed wild spattering and released less viscous lava than before. This led to the evacuation of parts of the village “Tacande”.

– The new vents produced a second lava flow. This moved in a west to south-west direction and was observed on September 21 south of the industrial area “Punto Limpio”, where it came relatively close to the main lava flow or even united with it.

– On the morning of 09/21/2021, the front of the main lava flow was just north of the center of the village “Todoque” and moved very slow. There were 183 houses destroyed and 106 acres of land covered with lava. 6000 people were evacuated.

– The sulfur dioxide emissions were determined on September 21, 2021 at 10,000 tons per day and had increased compared to the previous day (approx. 7,000 tons).

– On the afternoon of 09/21/2021, the tremor, which had decreased slightly after the onset of the eruption, increased significantly and remained high in the evening.

– The GPS stations in the west / southwest of the island recorded a further uplift of the area on September 21, 2021 despite the ongoing eruption. Overall, a maximum lift of 25 centimeters was determined.

– On the evening of September 21, the main vent produced sustained strombolian explosions or generated a lava fountain. The height of the fountain was roughly estimated by observers at 400 – 500 m.

– On the evening of 09/21/2021 at around 8:00 p.m. (local time), a new vent that had developed on the western flank of the main cone was visible. There were individual strombolian explosions there, as well as the release of a viscous lava flow. The front of this flow was moving in a westerly direction.

– On the evening of 09/21/2021, the main stream came closer and closer to the center of “Todoque” and threatened to block the important LP 213 road. This leads down to the coast to the towns of “Puerto Naos” and “La Bombilla”, which have already been evacuated, as well as the Hotel “Sol” near the beach of Puerto Naos, where 500 tourists were.

I have compiled this information from various websites and this blog. Main sources:

https://news.la-palma-aktuell.de

https://emergency.copernicus.eu

This summary is certainly not complete and is not free from errors. But I hope it helps to keep track of the events.

Oliver

3.1 mbLg N FUENCALIENTE DE LA PALMA.ILP

2021/09/30 08:23:57

13

https://twitter.com/RaphaelGrandin/status/1443487501218353153

Lava reaching the sea in the #LaPalmaeruption yesterday. Combo of @capellaspace radar image & @planet optical image.

Beautyful satellite image. How long soes it take to built on the delta? Streets? Foundations for houses? Todoque-Church II?

https://twitter.com/VolcansCanarias/status/1443516937263255561

Biger explosions again…

https://twitter.com/RTVCes/status/1443522907288834053

1 hour ago…

There are a new vent or fissure opening behind the main volcano cone… you can see it here:

It looks like the central island has started floating on the lake, which is now 13 meters deep. The west vent cone might have also disintegrated under the lava and risen to the surface.

It is very hard to get a real accurate scale but the tallest fountain seems to still be several tens of meters tall, about 50 meters even, blasting through 13 meters of lava. I dont know exactly if this is typical it is not easy to get that information, but last year the fountains were drowned by as little as a few meters, even the almost subplinian 1959 fountains were drowned under less lava than we see now, so clearly there is pressure behind this and the fact it will not be relieved if this goes on long term should at least put a bit of a warning on an ERZ eruption.

Back when it was new, there was a talk of calling the island Moku Nui, though it was never serious. Maybe it should be, it is being remarkably persistent, and could well survive up until the lake drains again, named features have been less persistent before…

That intrusion about a month ago towards the SW rift zone made me hopeful that we’d see an eruption in that zone rather than the ERZ. I much prefer the SW rift zone due to it being far less likely to threaten inhabited areas.

I wasn’t happy to see the signs of the ERZ reawakening.

Interesting point on the pressure required for fountaining through so much depth. That’s a lot of pressure.

Both rifts are open, the ERZ is clear open down to Pu’u O’o pretty much, and ongoing south flank quakes will allow magma as far east as highway 130, though it might need to fill Halemaumau properly to get the pressure to go that far. The only reason the eruptions now are in Halemaumau is because the bottom of Halemaumau is lower than anywhere on the rifts that magma has access to, when it fills eruptions will go to the rifts again.

On the topic of Keilar(sp?), is there any DI (inflation) occurring ? Does anybody have web links to the instruments ?

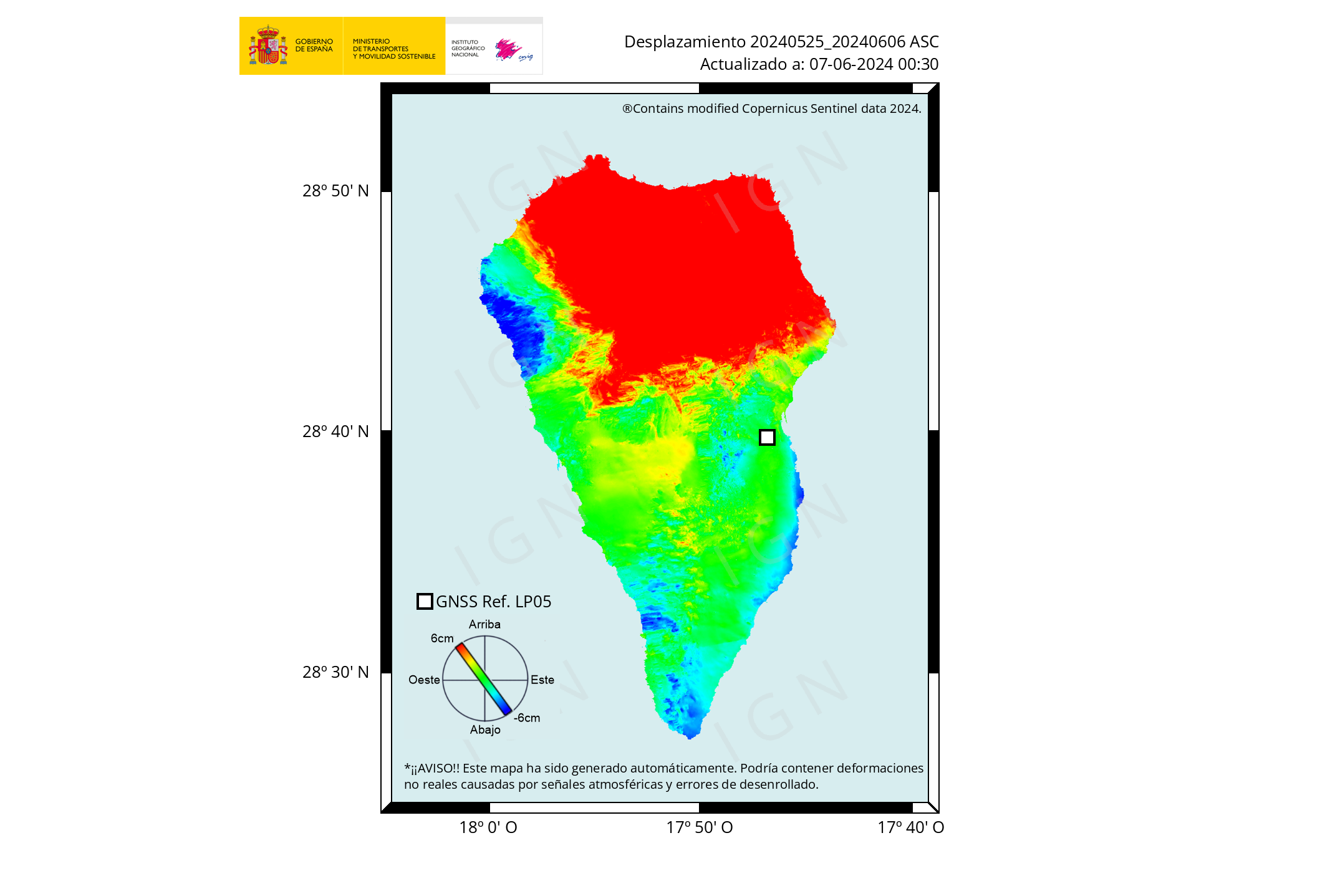

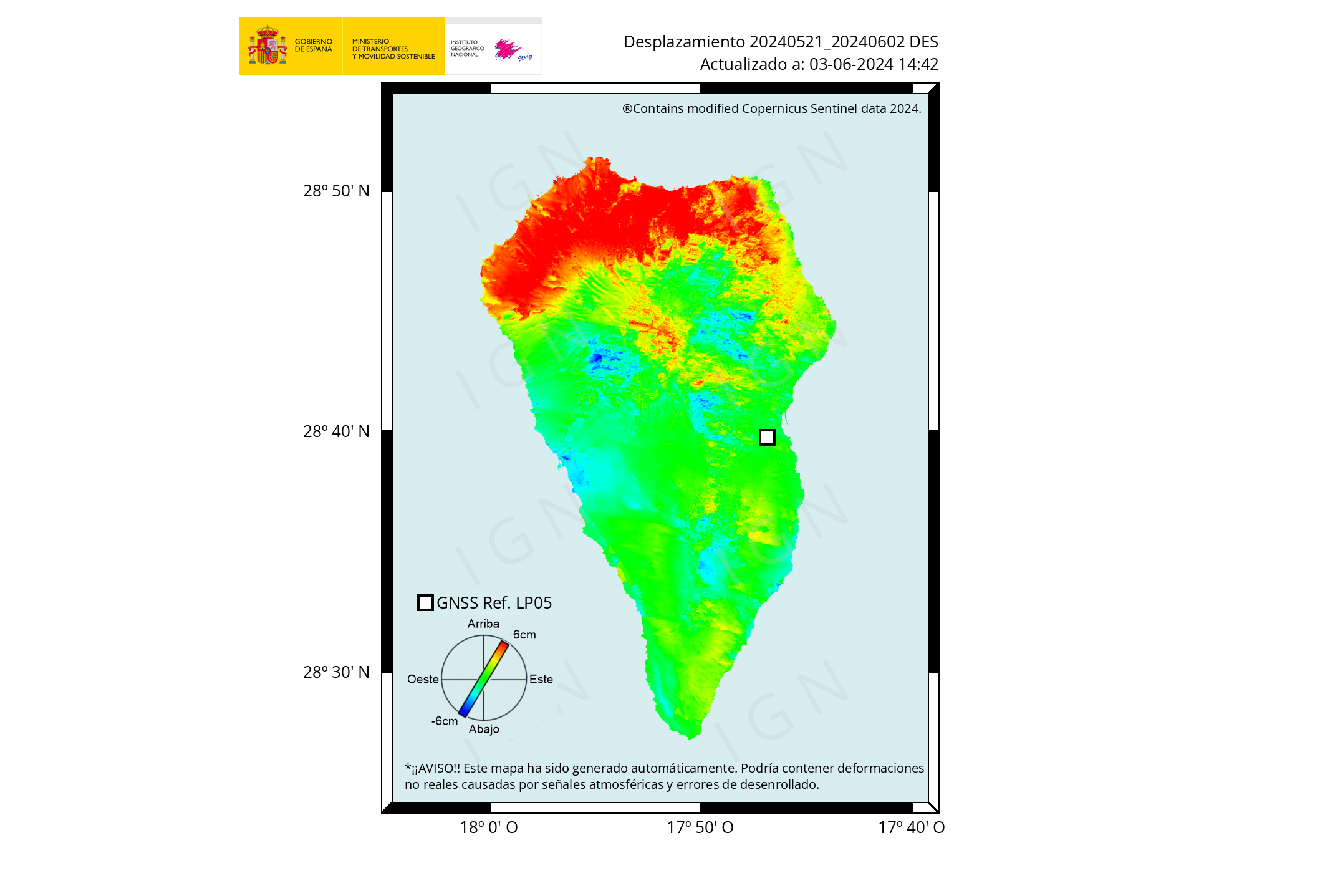

I read in an article that authorities are awaiting InSAR measurements to assess the situation. Let’s wait and see.

The GPS aren’t showing much, but it could be too early to show up a trend. Oddafell maybe travelling east or it could be a transient shift. They are trying to fix Oddafell though.

http://brunnur.vedur.is/gps/reykjanes.html

https://twitter.com/twinderseis/status/1443018983695863816

https://twitter.com/krjonsdottir/status/1443528643502919681

Bamm!! woke up just before 2 am.. M3.9 SW of Keilir. Swarm started 27/9. The automatic system has detected 1300 earthquakes in total when this is written..

Here are the non-verified quakes of the last days:

Source: https://en.vedur.is

A 3.5 this afternoon 0.7 km SW of Keilir.

It probably means pressure on the Fagradalsfjall system is increasing until the eruption restarts.

Big Jump in GPS since yesterday – especially towards the East.

Also seen on LP03, LP04, LP05, MAZO

Link and location of stations https://www.ign.es/web/ign/portal/vlc-gps

I don’t like it… max inflation again and many deep quakes… not good!

I’m puzzled. Yesterday IGN reported this (translated) https://www.ign.es/web/resources/volcanologia/html/CA_noticias.html

And they had the LP03 chart from yesterday to illustrate that.

Today when things have jumped even more they say

I have done some numbers and it turns out that during the initial 1 hour and 20 minutes of eruption at Kilauea the eruption rate averaged 980 cubic meters per second! Although Kilauea may not look so threatening it is actually capable of very strong eruptions, they can be as intense as those of Mauna Loa, as demostrated by the current event, and with very little warning.

The eruption slowed down a lot after the first hour. Halema’uma’u eruptions have a powerful but very brief initial phase then decrease exponentially. As of now 7 million cubic meters have been erupted.

I did the calculations with the lava lake depth data of HVO, and its area of 45 hectares:

https://www.usgs.gov/volcanoes/kilauea/past-week

Same sort of thing for the eruptions in 1974, all 3 of them. 1000 m3/s eruption rates then rapid drop often to complete finish within a day. Seems perfectly characteristic of a magma chamber pressurized and rupturing.

Mauna Loa doesnt have magma storage in its rifts so the dikes can go a long way down, where gravity starts to get involved, that is probably why its eruptions are big. Kilauea basically has ‘summit’ eruptions all along the rift too, though sometimes long dikes can form too like in 1840. But 1840 was not a typical LERZ eruption more something like 1968 but a lot bigger, an upper ERZ eruption that got lost… 🙂

Seems to be ash falling where the tvlapalma camera is. Not heavy but noticeable, you can sometimes hear it hitting the camera.

And plenty of quakes between Litlihrutur (not far north of the current eruption) and Keilir to its north in Iceland. Could that mean a new eruption?

On the IGN report, yesterday, we can see the earthquakes has found on the “deep magma chamber”, new magma inyection….. Not sure, but I wait that not have a new “vulcano incoming” as 1940s eruption.

https://www.ign.es/web/resources/volcanologia/SIS/PA_SIS_relocs_new_20210929.mp4

See the deformation…. 26/09

28/09

La palma has starting rise from the west on some sectors….. a incoming event ahead?

That’s great… all island is inflating now… not!

Those NEW GPS readings look suspiciously like a bad set of data points (instrument or processing glitch) . Let’s see what the instrument readings tomorrow.

That’s what I hope but the same East signal is across lots of stations on La Palma but it doesn’t show up on any of the other islands, nor is it of the exactly the same magnitude across the different La Palma stations – seems weird if it’s a glitch. But as you say let’s see tomorrow.

Could this be attributed to the ash laying on the ground?

possibly, but i am not a GPS guru . Retired Geophysicist, only …

Re “But the signals are purely rock cracking. No signs of magma or fluids on the move. Yet…” (Clive)

I’d be interested – how would slowly moving magma without degassing look different from what we see in the tremor plot?

When I’ve seen stuff like magma and steam cracking rock, the sharp quake signal is followed by tremors that kind of shows further cracking and vibrating as lava and steam move through the opening. Once done it goes quiet. Kind of like this:

As I say, I am a total dunce on this stuff and this is what I learnt from the experts here.

Gulp. I hope I’m right!

Ah, I see what you mean. Thanks a lot!

So (assuming this is true), something would have to create a lot of very local tension then, in order to generate such a localized swarm not caused by a local feature (like the tip of an advancing magma movement)? Like some structure that focuses the global strain to that particular point; but does not release all the pressure in a single event?

I am sorry, I truly am. But I don’t understand your question.

My take on the seismic records is that the signals are simply rock cracking. There could be two reasons for this: first is ‘pull’ pressure from Iceland’s MAR tectonic movements pulling the fault apart, second is pressure from an intrusion from the MOHO.

If I recall rightly, the general take on Fagradalir was the tectonics pulled the fault open and the ready-and-waiting intrusion took advantage of the opening door.

So…at a wild guess…I would expect to start seeing the longer quake signals and tornillos turning up as the magma intrusion starts invading the gap. And I reckon that could be quick.

All that said, please remember I am an imbecile. 🙂

Basically, I was just surprised that if there is only “dry” rock cracking (without the tip of some magma flow pushing forward) why that would be localized, with many quakes, to one spot. (And even a moving spot).

If it would be dry rock breaking due to some force (like shear from the rifting), I would have expected cracks to appear randomly along some line or in some area, to relieve the forces everywhere along the boundary between the parts that are moving relative to one another and build up that force.

So if it is the pulling force pulling the fault open, somehow it feels like there should be cracking along some longer segment of the fault. But maybe it is just a single propagating crack?

(But most likely I just have no clue)

https://twitter.com/VolcansCanarias/status/1443575525646037010

A field of fumaroles appears on the north slope of the cone. It maintains a large emission of lava in the lower mouth and strombolian activity in the upper ones. Images from El Paso Cra.

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/FAicSfjVIBECAMa?format=jpg

More pics

https://twitter.com/VolcansCanarias/status/1443576229009920005

I wondered what was happening when I saw them this morning, wasn’t sure if they weren’t low cloud spilling over the cone. Thanks for the update. Looks as if Palma has plenty more surprises up its sleeve. Just a shame its an inhabited area.

I would wish to qualify what I’m saying very heavily,because I have no expertise in any related field.

But when I look at those fumaroles, it looks to me that I am seeing a steep slope which is about to give way.

I’d be headed in the opposite direction.

https://twitter.com/involcan/status/1443585967164583940

First thin-section images of #LaPalmaEruption lava, being made at

@ULL

and

@CanalUGR

. These rocks contain useful crystals and bubbles to understand the magma and eruption.

Explains why it turns to Aa lava so quickly the high crystalinity and relativly low temperatures.

But Are these samples from close to the vent?

They didn’t told… at least i don’t know.

Events at Keilir in the last few days are beginning to feel like sometime about a year ago when >M3s on the dike didn’t get commented on, but all the same:

Thursday

30.09.2021 13:54:16 63.936 -22.180 6.2 km 3.5 99.0 0.7 km SW of Keilir

10 minutes before this eq there was a report on RUV, from which the following is an excerpt. (It also appears from the report that the authorities have up to date InSAR imagery, which will, presumably prompt more reporting.)

Via Giggle:

Páll Einarsson, a geophysicist, says that this [the raised seismicity, I think – am57] can actually mean everything possible.

“So far, there does not seem to be much crustal movement accompanying these earthquakes, so there is probably not much magma movement in connection with this. But that cannot be completely ruled out, “says Páll.

He says several scenarios are possible: “First of all, this could mean that the magma channel, which has been running for 6 months, is changing and that an eruption is taking place in a new place. It can not be ruled out, we know examples of it from the Surtsey eruption for example, then seismic activity was related to when the eruption went from one eruption site to another, “says Páll.

“Another scenario would be that this represented the end of the eruption, we also know examples of that; Hekla eruptions sometimes end with a slight earthquake. And it could also be that there is tension there to level out after the walk, “says Páll.

“We must not forget that the eruption that has lasted for 6 months is part of a much broader scenario that covers the entire Reykjanes peninsula. This could be a part of it, but it goes without saying that there is a new part going on in this scenario that is a good reason to watch very carefully. ”

https://www.ruv.is/frett/2021/09/30/snarpur-skjalfti-vid-keili-nytt-skeid-hafid

Assuming magma still wells up…

Current swarm takes place between 5 and 8 km depth. No progress upwards (yet). Apparently the crust above is a difficult obstacle to overcome.

If Fagras conduit is blocked, closed, chances for a new eruption site somewhere along the dyke formed in March are growing.

https://www.ruv.is/frett/2021/09/30/reykjanes-enters-a-new-phase

English.

I think Fagradsfjall has come to an end. There doesn’t seem to be another pressure to keep going.

But the peninsula will likely reawaken within the next 20 years.

On the plus side,

Kilauea just restarted

Grimsvotn slowly parting

Askja inflating

Katla shaking

Etna broken-hearted

John Tarson, aka EpicLava, recently live-streamed on Facebook that the fountains are visible over the rim of the caldera.

https://fb.watch/8lCEboRX90/

At Kilauea, I meant to mention.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=dakpaosE6_U

La Palma ocean entry is going strong

The lava flows are well channelized now

Can you find anything on why fumaroles are on the north side of the cone complex? I would not think that this is a good sign, to see gas escaping low down, but the cone is porous since it was mostly ash material.

It may be passive degassing–possibly from the original fissure. Also, this may be the location for a future pit crater, similar to the Kilauea Overlook fumarole that turned into a pit crater / lava lake.

Clear shot on Vesta TV youtube

is that live or old? Wind strength seems much more that other cams

That’s yesterday’s view

Yep, recording – sorry

On Afar live feed looks like the thing is under water

By Pek https://www.meteopt.com/forum/topico/actividade-vulcanica-2021.10597/pagina-22#post-839633

The whole local ecosystem been exterminated 🙂 the earthworms are cooked

The soil turned to charmotte under the lava flows

wow! Thanks for posting that Luis, as it is brilliant to see the actual change in the landscape. I hadn’t realise how high the cone had grown so thanks again.

Thanks!

This is very useful, thank you!

great post, Luis.. really helps to see how things have changed.

Wow

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=jfFj1V7l1YQ

https://twitter.com/USGSVolcanoes/status/1443640215407677441

Lava fountains reach height of a 5-story building as #KilaueaErupts. Beginning Sep 29, lava fountains appeared on surface of the lava lake within Halema‘uma‘u crater. Video shows dominant fountain south of the lake center.

Why? The fresh magma just needs to contain enough gas. If that gas expands once tha magma reaches the lake from below, the expanding gas bubbles will continue to pull the magma all the way up through the lava lake. So it’ll be half vent-driven, half bubble-driven. But 100 feet is certainly no problem in a 200m deep lake.

Thanks for that reply, you have given me something to think about.

3.4 mbLg NE FUENCALIENTE DE LA PALMA.IL

2021/09/30 18:50:29

13

This is becomming a large eruption.. the Basanite wont stop flowing

This lava fountains are impressive!

This is becomming a large eruption.. the Basanite wont stop flowing .. still perhaps not as fluid as 1949 yet

And tremor is also rising again. The question is whether the existing vents are still sufficient to carry the rising magma out or whether a new vent or even a new eruptive fissure is developing somewhere. Perhaps, as in 1949, a volcano like Duraznero in the “Cumbre Vieja” mountain range will become active. The magma would simply have to rise vertically.

Luis, I am concerned about the uplift shown on the LP03 GPS station. It is starting to rise again and go even more south. I believe we’ve seen re-injection of fresh lava into the cone complex but this would signal more on the way shortly.

I’m very worried too… for me this will lead to an increase of eruption… maby the reactivation of main Cumbre Vieja cone?

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-10045157/Largest-underwater-eruption-recorded-gives-birth-enormous-2-690ft-underwater-volcano.html is an interesting article about the development of a brand new underwater volcano of significant size. Apparently magma came from the mantle crust boundary zone.

Big Island video news has some footage of the new eruption.

The residents of four neighborhoods of Tazacorte remain confined. The gases released by the volcano are very toxic. We saw it in # Tn2Canarias

2021-09-30 20:30:12.2

04min ago

28.53 N 17.85 W 19 4.0 CANARY ISLANDS, SPAIN REGION

El Instituto Geográfico Nacional de Sismología ha registrado un nuevo #terremoto en #LaPalma en la zona de Fuencaliente de magnitud 4.0 a una profundidad de 15 kilómetros.

@IGN_Sismologia

The last earthquakes has arround the Duraznero / El Charco old Vulcanos. A repeat of 1949 eruption?

3.5 mbLg SW VILLA DE MAZO.ILP 2021/09/30 20:30:12, III Intensity, 13 Km

3.4 mbLg NE FUENCALIENTE DE LA PALMA.IL 2021/09/30 18:50:29, 13 Km

3.0 mbLg SW VILLA DE MAZO.ILP 2021/09/30 18:49:48 12 Km

EVENT: es2021teqei 2021/09/30 20:30:12 28.5790 -17.8483 13 3.5 SW VILLA DE MAZO.ILP

Updated 2021-09-30 20:46 UTC

RATIO OF INTENSITIES (EMS) AND POPULATIONS

IN WHICH THIS EARTHQUAKE HAS BEEN FEELED :

III BUNGALOWS DE TAJUYA, LOS LLANOS DE ARIDANE.TF III CARDÓN, TAZACORTE.TF III LA CONDESA, LOS LLANOS DE ARIDANE.TF III LAS INDIAS, FUENCALIENTE DE LA PALMA.TF III LOS CANARIOS.TF III LOS LLANOS DE ARIDANE.TF III TENISCA MOUNTAIN, LOS LLANOS DE ARIDANE.TF III TAJUYA, EL PASO.TF II-III ARGUAL, LOS LLANOS DE ARIDANE.TF II-III EL BARRIAL, EL PASO.TF II-III EL PUEBLO.TF II-III HERMOSILLA, THE PLAINS OF ARIDANE.TF

II-III LA LAGUNA, LOS LLANOS DE ARIDANE.TF

II-III LOS PEDREGALES, EL PASO.TF

II-III LOS PEDREGALES, LOS LLANOS DE ARIDANE.TF

II-III PUERTO, TAZACORTE.TF

II-III RETAMAR, LOS LLANOS DE ARIDANE.TF

II-III ROQUE DE ABAJO, SANTA CRUZ DE LA PALMA.TF

II-III TAZACORTE.TF

II-III TENDIÑA, LOS LLANOS DE ARIDANE.TF

II-III TRIANA, LOS LLANOS DE ARIDANE.TF

II DOS PINOS, EL PASO.TF

II MALPAÍS DE TRIANA, LOS LLANOS DE ARIDANE.TF

II SAN ANTONIO, BREÑA BAJA.TF

You sent

Look how much its been felt over the island

Continue raising (IV)

https://www.ign.es/web/ign/portal/ultimos-terremotos/-/ultimos-terremotos/open30Spain?_IGNGFSSismoSismicidadReciente_WAR_IGNGFSSismoSismicidadRecienteportlet_formDate=1633037371257&_IGNGFSSismoSismicidadReciente_WAR_IGNGFSSismoSismicidadRecienteportlet_evid=es2021teqei

EVENTO: es2021teqei 2021/09/30 20:30:12 28.5790 -17.8483 13 3.5 SW VILLA DE MAZO.ILP

Actualizado 2021-09-30 21:31 UTC

RELACIÓN DE INTENSIDADES (EMS) Y POBLACIONES

EN LAS QUE SE HA SENTIDO ESTE TERREMOTO:

IV BARRIAL DE ARRIBA,EL PASO.TF

III ARGUAL,LOS LLANOS DE ARIDANE.TF

III BUNGALOWS DE TAJUYA,LOS LLANOS DE ARIDANE.TF

III CARDÓN,TAZACORTE.TF

…..

http://www.ign.es/web/ign/portal/sis-cuestionario-macrosismico shows 17 quakes today and 21 yesterday. We have 2 hours left to go for Sept 30th.

Deep 2.9 quake on Kilauea’s southwest rift zone.

https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/hv72735722/executive

Earthquake swarm continues near Keilir. https://www.ruv.is/frett/2021/09/30/earthquake-swarm-continues. Now they’re saying over 700 quakes occurred, and another news spot say 1100 quakes have occurred in this swarm.

I reckon we’re going to see a new eruption in that area. This is the sort of pattern that preceded Fagradalir.

So I’m calling it! 9 October at 1:25pm.

(‘m pre-boiling the eggs now, so I can rub them over my face when it fails to arrive.)

Nice! Let me throw the 07th of October at 11:26 into the hat! Any more bets and bravery?

What is the reason that the Cumbre Vieja volcano has such an activity type separation as to play blowtorch on one vent and a spring of splashing lava on another?

What internal “facilities” must have come into existence for that to happen?

I think I can see a hint of a glow…

…from the crater at Fagradals volcano…

https://www.mbl.is/promos/elgosid-i-beinni/5/

Good catch. You are right, the cone has turned the illumination back on. We could have three volcanic islands erupting simultanesouly

🙂

remor also looks to be increasing.

Good catch!

My two guesses are that either the tourist office finally got around to replacing the lightbulb, or what we’re seeing near Kielar isn’t an intrusion.

My current guess, if guess #2 is correct, is that what we might be seeing is a reinflation of the original intrusion from back in March. If so, I’d keep a close eye on the cone, and especially the area west of it (where we saw the lava fountains/vents in the lava lake last time). If it’s going into the lake from underneath, the clue I’d look for is moss fires at the edge of the lake (an indication it’s rising).

https://twitter.com/involcan/status/1443689769012277250

New images of the lava delta at 16.40 (Canarian time)

What about that south lobe? Is it going to chew up more territory and carve a new path to the ocean?

Sorry I meant this picture, on the same twitter page as your post https://twitter.com/tasagronomos/status/1443625321144664066

https://world3dmap.com/interactive-map-canary-island-volcanoe-lava-flow/ has an interactive map from the IGN which you can pan in or out and click on the icons to get information. For some reason I cannot seem to find the original IGN webpage for this very interesting interactive map. They have updated the lava flow into the Atlantic Ocean, so it is current.

Found the earthquake traces 3d charts – near the bottom of the web page – https://www.ign.es/web/vlc-serie-palma. It is interesting to see a retrace of the deeper quakes again and then another one back into the upper green zone, which indicates that we have a fresh batch of hot magma ascending

Those are the lights from a town (Reykjavik?) in the distance?

https://www.mbl.is/promos/elgosid-i-beinni/11/

I’ve been trying to figure out which town those lights are from.

My current guess is Kaflavik.

They turned the camera towards Keilir which means Reykjavik is now in the background.

Could this be the eruption at Keiler?

I’m pretty sure that’s the lights from Reykjavik.

Seismic and drumplots do not show any eruption. Also, you can be sure the Iceland volcano experts would be on it like a rash!

It is. It says so in the description.

The lights in the background behind Mt. Keilir are from the capital area.

Bets way to separate the background habitation from the volcano light is by comparing to the previous night. The background remains (if not clouded out). Last night’s brightness was coming from the rim of the cone.

Don’t think the earthquakes are shallow enough yet for an eruption (unless there have been some more since I last looked).

Think it is still a case of watch this space (quite a big space – at least between Kelir and Fagradalsfjall).

I could be wrong …

Could that be the sun coming up, the one with the bright centre field?

OK that was silly. 5 hours or so to go!

I am watching this channel “DIRECTO | Erupción del volcán en La Palma”

Around 16 min before 8:05pm EST there is a change a La Palma where the first effusive vent (there are two now) starts a large flow helped by the smaller vent just above it. Nice sheet down the cone.

Detail of the “Baja Isla” or lava delta from IGME-CSIC and near the end you can see the lava cave off and fall into ocean depths leaving a sediment trail as cave-ins occur. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rFkNG3_UF1g

We seem to have two fountains behind the lava outflow now at La Palma? Apologies if this is late and boringly repetitive observation.

I noticed after mapping the new vents at Kilauea that the vents on the side of the cone, the old west vent and the new, are along the trace of the southwest rift. The surface fissures are aligned with the crater geometry but the deeper trace is exactly the same as where vents appeared in the crater during the 20th century. It looks to me like yet more proof of the deceptively shallow nature of the 2018 collapse.

2018 was only the shallow Halemaumau system and only a fraction of that, like a bigger version of 1924. The deeper structures of the volcano are all untouched, though the ERZ connector might be bigger and more open after having so much lava draining through it in 2018. The reason for eruptions here is just gravity, it is a deep hole and the bottom is lower than most of the rift, activity will go back to pre-2018 styles easily.

La Palma. Forest fire caused by lava bomb? Or something more sinister?

Forest/grass fire, methinks.

That fire has some heft to it now. There’s a couple of houses that were to this point isolated but seemingly undamaged.

Is this from a new vent? seems like a lot of flame https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jfFj1V7l1YQ (timestamp: 3:41 am La Palma time)

3:51 am La Palma time, big eruption of flame in the middle of the view.. definitely 1 new vent open to the lower right, did a new vent open on the lower left, fueling these fires?

There is a lava flow coming down from the left now, behind that little hill.

The glow is quite telling.

Are new vents opening up? One in the lower right just now started around 3:43 am La Palma time https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jfFj1V7l1YQ

Wow the lava is really fluid now, looks just like the lava in Hawaii. Not easy to tell, the fire might just be an actual fire, but with the lava the way it is now I would expect it to start leaking out of the cone, or out of the ground around it, and the lava bombs are not exactly flying off in that direction or that far.

This really looks exactly like what a kid imagines a volcano looks like 🙂

The lava is smoking more now, apparently more sulfur, and you can see the new vent on the lower right and there is some vent hidden by a hill, but shown by the dull red glow, to the lower left.

Not as easy to see as I thought, but the location of that new vent is about where the red line is, the one outside the mapped lava.

https://imgur.com/a/oLCHrFL

The scene at 4:40:59 pm La Palma time https://drive.google.com/file/d/11cdPocH3M-Dd7FkVFE-w22tZ633xnL3u/view?usp=sharing

The new fluid lava is really tearing the side of the cone apart, it looks a lot like all the pits that formed on Pu’u O’o in the 1992-2007 era only in this case the cone is still being formed at the same time.

Earlier on in the stream it zoomed on the left flow, the open channel is flowing like water, I woudl say it is of comparable fluidity to the pahoehoe in 1949, or at Kilauea or Fagradalsfjall, proper hawaiian eruption now, must be very hot lava.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rFkNG3_UF1g

Impressive, in what short amount of time this huge delta has formed. Maybe, because of the depth of the ocean, other than in Hawaii, La Palma doesn’t go that steep down.

Soon it will be going over a 150 m deep submarine seacliff

That will be much more steamy

Why so?

If the lava drops into deeper water it will sink more quickly, so more of the heat will be deposited more deeply, distributed into more weater volume; generating less steam at even the same temperature (due to higher pressure) and the steam that is created has to rise through a longer water column (meaning it is filtered more, and more will be re-condensed into the water).

I would assume that lava into a few 10 feet of water is the worst case, after that, the deeper the water, the better (in terms of reducing “laze” vapor).

https://youtu.be/iRcs7KoiURg At 06:24:58 a new vent opened up at the bottom of screen with white hot lava and I believe the there is a fissure line at the bottom behind the hill as i have been watching this for a couple hours now

Repeat at 06:40:40 am and seeing a white hot jet emit from a dark hillside is a bit unnerving. Same location

Cant see the source exactly, but the camera did turn down the exposure and it is most certainly a lava flow. The close up of the dominant effusive vent also shows the speed of the lava, it is just like the lava flows in Hawaii, as fluid as it gets.

Maybe this eruption is a change from the others, I dont recall there being any real long term flow like this in the 1971 or 1949 flows, at least nothing close to this intensity for more than a few hours. Im not talking an eruption like on Lanzarote that lasts years and buries half the island eventually but something rather above average for La Palma.

Daybreak this is actually a big deal, the new lava flow isnt even connected to the existing field at all, we have new more distant vents opening. Maybe this is like in 1949, or the long fissure downslope of the 1712 cone, but then for this to happen with such a powerful effusive vent already open brings a lot of questions.

The UME (Emergency Military Unit), has confirmed them, 2 new lava flows at north, over the industrial poligon zone. That lava flows apears at 2:00 AM local.

https://youtu.be/dxIlWtcq4g4

I first noticed them around 4 am local time or so.. quite surprised to see this

On the RUV cam we can see a lot of smoke at the moment. However, the MBL cam rather clearly shows it’s not from the cone.

It appears there’s a lot of smoke coming from Geldingalir.

A couple of days ago, I said that smoke from Geldingalir moss fires indicates the eruption is underway. I now see smoke, and it looks like that sort of smoke. So, I guess I have no choice but to follow through and call it: IMHO, the eruption at Geldingalir has began – and began at least 24 hours ago.

I have a hunch there’s a hefty serving of crow in my future…

The meradalir timelapse cam does show some glow, at least strong heat, both at the crater and at Geldingadalir. Theres also some incandescent but dim holes on the livestream of meradalir by MBI, its definitely not dead just building pressure to erupt again. I said this last time that Pu’u O’o went weeks to over a month with no lava visible at all, but always came back as though nothing changed. Maybe deep down towards Keilir there is more magma storage, pressure builds there, before releasing at the cone.

It is very hard to kill an open conduit, the only way we have seen it happen is to induce a total collapse so that it fills with material. This is the case at Kilauea, Nyiragongo and Ambrym, and in fact 2 of those have even woke up already,. Fagradalsfjall also has a difference to these in that its conduit goes all the way to the mantle, so you have to close it off all the way or ut will eventually reform again. This area is going to be a frequent appearance on the Iceland eruptions board for the rest if our lives if you ask me.

I think you’re right.

IMHO, what’s been going on near Keilar is the conduit from the mantle indicating that it’s still flowing.

I don’t know the URL of the camera itself (I wish I did) but AFAR youtube has a view on camera 2 into part of Geldingalir. In it, I can see a heck of a lot of outgassing coming from the lava surface roughly where those new vents occurred after the last hiatus. Right now, 9:44 Iceland time, it’s going quite strong at the center of the upper frame.

The image Luis linked yesterday

has a very sad message: the wide southern branch of the flow overran so far unharmed areas of Todoque.

Or is there hope that the area is wrongly classified by the algorithm that detects lava surface? The Sentinel image from yesterday doesn’t have the southern branch, neither have OSM and the Copernicus estimate from today.

Oh, I just realize that this ‘southern branch’ was on the OSM & Copernicus maps all the time, sorry. (Sad anyway.) Antonio Carillo’s drone flight shows this branch clearly.

YT…/watch?v=Zs-7bY48N5A

Good news: The southern parts of Todoque are unharmed, so far. Let’s hope it stays like this.

This is so legendary:

Before: “Will be a small basanite eruption.” “La Palma is a very weak hotspot.” “… etc.”

After: Shining lava flows that are all around Cumbre Vieja and no close end in sight.

Looks about equally amazing as Fagradalsfjall looked in its effusive phases 🙂

Compared to Hawaii or Iceland this is small, but most volcanism is really, we have been spoiled by Kilauea and Bardarbunga.

Canaries are not erupting all the time, so output long term is not high, but during an actual eruption that is not really relevant, there is no shallow magma chamber so supply rate and other terms we use to talk about Kilauea and etc are not useful. What is useful is that there has been apparently a decade of buildup to this eruption, and it is erupting at a high rate compared to recent predecessors, so it is going to erupt a lot more. I expect it might even overtake Fagradalsfjall, though Etna could be a bit out of reach and Kilauea might have just thrown us a wild card.

It isn’t going to become a lava flood, but it could be an example of the biggest eruption these islands can do. Lanzarote was basically what we are watching except it kept going for 6 years, and the major vent changed at least as many times. Doubt that will happen now but then who knows at this point, maybe Cumbre Vieja has been mostly asleep in the Holocene, woke up 500 years ago, and this is when it has decided to catch up… would be nice to get accurate dates of prehistoric eruptions but GVP hast got much there.

I think something lime a pause must have taken place in Cumbre Vieja which allowed erosion to create those cliffs where the lava is flowing down, many of the platforms under those cliffs are from historic or very recent eruptions, so more active phase in the last 500 years? (for canary standard)

The volcanoes of the Canary Islands seem to be dominant for a certain period and then go dormant for long intervals of centuries or thousands of years.

Lanzarote hadn’t erupted since 20,000 years ago, when La Corona volcano formed, but then throws 2 eruptions in rapid succession in 1730 and 1824.

Gran Canaria was very active 3000-2000 years ago when it formed several lava flows.

Tenerife is always frequently active, but its eruptions were much more bigger and volumous 1000-2000 years ago. It produced a series of flank and summit phonolite eruptions, Montaña Blanca which was probably over 1 km3 and had a subplinian phase, Roques Blancos which erupted 2 km3, the eruptions which formed the summit of El Teide, and Montaña Reventada. These eruptions lasted a very long time, years or decades, except Montaña Reventada whcih was fast and may have drained away the conduit of El Teide.

El Hierro hasn’t produced any subaerial eruption in historical times since 1492, even though its surface looks similarly young to La Palma. It must be in a low activity phase, at least until 2011. Its prehistoric eruptions are sadly not dated, although there is some research ongoing, I think.

La Palma had a long dormancy between the 1000 AD eruption of Nambroque and the 1480 eruption of Montaña Quemada, but then it has erupted 7 more times after Montaña Quemada. Its eruptions seem to be getting shorter too, perhaps because they are increasingly intense. There is no proper dating of prehistoric eruptions, though it looks like there was some big stuff 3000 years ago, when a very voluminous possibly long lived eruption of Montaña del Fuego happened. No activity is known between 3000-1000 years ago, but it is hard to know if this was a time dormancy or if undated eruptions took place.

Roques Blancos didnt return a location on google maps but I assume it is the light coloured area east of Teide, there are lots of flat domes there. It looks like it was not too viscous, definitely nit like we see in basaltic eruptions but the lava still manages to flow away from the vent easily, just very slow I imagine, like a gigantic pahoehoe toe.

Montaña Reventada looks to be one of a few similar eruptions in that area. Maybe the eruption now on La Palma will end up being a lot like that.

Interesting Teide has no caldera, it is exactly the sort of place to expect one, a massive volcano that has both silicic eruptions and low altitude mafic vents along extensive rift zones, yet it is standing there still tall and majestic. Maybe that is for the better though.

Some info about Holocene Tenerife volcanoes:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0377027319306250?via%3Dihub

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0377027320301098?via%3Dihub

That white area is Montaña Blanca. Roques Blancos is on the west side of El Teide. This geologic map shows the various eruptions:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233747053_Geological_map_of_the_Teide_Volcanic_complex

I think that the mafic eruptions should be considered eccentric, while the phonolitic eruptions represent the shallow system of El Teide.

Teide has a 16x11km caldera, or at least the precursor volcano has. The Las Canadas caldera which was likely a medium VEI5. How have you missed this!

I mean its still small, lets be honest haha “I’ve seen bigger ones” kind of situation and so far only 2 weeks, sadly we have no other monitored eruption in la palma to compate deformation quakes etc

Looks like the fumaroles up slope from the vents at Palma are back, just as yesterday morning. Maybe they are just better illuminated at this time of day. Lots of ash showers.

With better drone coverage, it’s clear that the top of the cone–in all directions–is fumarolic. Less likely that a fissure opens uprift, but I still think it proscribes a potential pit crater.

New vent…

https://twitter.com/RTVCes/status/1443830711388155914

Regarding the Keilir situation, here are the latest (non-verfied) quakes. I categorized the events in groups. It shows that a stronger and less strong quakes happen in different areas. One might or might not see a very small negative trend in the depth, certainly not significant.

Very nice! The peaks (Keilir etc.) are where the triangles are, or where the first letter is?

The peaks are where the triangles are. I hacked the coordinates manually, so there might be some margin.

You did such an excellent job with this the last time, getting the fissure to within 500 meters or so of true location. Please keep up the great work Quinauberon (I personally feel you did better than the IMO)

From involcan Twitter:

Vídeo a las 10.00 h (hora canaria) tomado por nuestros compañeros en el campo. Nueva fisura y nueva colada de lava / Video at 10:00 am (Canarian time) taken by our colleagues in the field. New fissure and new lava flow #erupcionlapalma #lapalmaeruption #lapalma

https://twitter.com/involcan/status/1443869219146420227?ref_src=twsrc%5Egoogle%7Ctwcamp%5Eserp%7Ctwgr%5Etweet

https://twitter.com/involcan/status/1443871260803584010

The new vent is a significant distance from the main one. Is this an area previously untouched by lava? There’s been lots of ashfall there.

Screenshot

New vent drone video:

https://youtu.be/e2LhyigLZYM

It is very nice to see today what I could NOT see last night when watching the new vents open up.